I have a talent for lying. People don’t believe me when I say this. It’s the Midwest in me, rooted deep— the tendency for enthusiasm and sympathy, the tics of “sorry” and “ope!” that shoot out despite my best efforts and ten years of distance from Iowa. It’s okay; I understand. I, too, prefer to think of myself as truthful. “But no, really—” they say, “You, lie? I don’t think you can. Here, do it right now.”

My dear, I want to tell them, I’ve been doing it the whole time.

Most people don’t like to think of themselves as credulous. Most people (especially in this city) imagine they’re keen observers—if not worldly, then at least students of human nature. Most people are wrong.

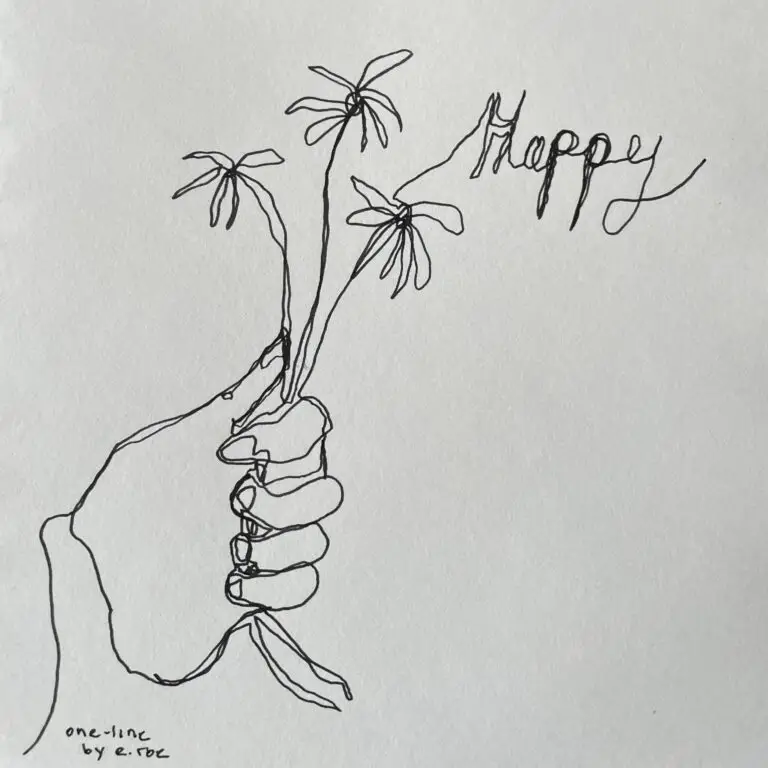

Have I ever been caught? Only once. I was six or seven, my mom and I still living with my grandparents in their house in what was then a mostly rural part of Des Moines. There were a few planned communities out there, separated by miles of soon-to-be foreclosed farmland. All the homes in my grandparents’ community had large yards, fenced only by lines of foliage planted to mark the property boundaries. I was playing along the edge of ours when I saw a patch of daffodils, deep yellow like melted butter. It was the color, really, that reminded me of my mom’s perfume, the bottle stamped on the glass front in just the same hue, with a single word: Happy. I grasped three flower stems in my fist, and, pulling gently but consistently (as my grandmother had taught), tugged them out of the ground by the roots. When my mother returned from work that evening, I presented them to her with pride, expecting her to see the consanguinity of my choice, the color of the buds, the perfume bottle, its proper signifier—Happy —and for recognition to be conjured on her face. Not so.

“Where did you get those flowers?” I can clearly see that something has gone wrong. “Over there,” I point, knowing already, intuitively, that the best lies flower from a seed of truth. “But they were already on the ground.” Mom knows otherwise. I’m lectured for violating the property rights of our neighbors, for stealing. My sentence is unmitigated by the generosity of my intent: No TV for me tonight, plus I have to write a humiliating apology note to the neighbors. In my shame, I vow to be better—and I will be. So much better that, for all my fictions, I won’t be caught in a lie for the next 26 years.

Today, I’m actually trying to be better—this time, about not lying. I’ve been through a lot of therapy, and I’m making it a point to at least cut down. A few weeks ago, I make a confession to my partner, spurred by a party-game question about our virtues and vices.

“Um, I guess … I used to lie a lot?” I offer.

“What, really?” I can tell he doesn’t believe me.

“Uh, yeah. But like, not to you! Not much, at least. I’m trying to be better.”

Now, he’s really interested. “Like, what kind of lies?” He asks.

“Uhhhh…” my brain rattles around for something appropriate to share. Not that. No, not Montreal. Not the girl from Boathouse Grill. Not that time you came up to his friends’ place in New Haven a day late.

“Like… saying I’m busy sometimes when I just want to be alone?”

“Oh. Babe, everyone does that!”

“Oh, yeah.” I laugh weakly. Even my self-consciousness is feigned. “I guess so. Guess it’s maybe not such a big deal.” He drops the subject, forgets about it. Just as I figured. Truth is, most people are only too happy to be deceived.